Efene: an Erlang VM language that embraces the Zen of Python

In this ocasion we interviewed Mariano Guerra, creator of Efene. Efene is “an alternative syntax for the Erlang Programming Language…

In this ocasion we interviewed Mariano Guerra, creator of Efene. Efene is “an alternative syntax for the Erlang Programming Language focusing on simplicity, consistency, ease of use and programmer UX”. After reading the interview with Mariano Guerra, check Efene Quick Introduction for the Busy/Lazy Programmer for learning more about Efene.

Why did you create efene?

I learn by doing, and a while ago I wanted to learn Erlang, it was the first functional programming language I wanted to learn coming from C, C++, ASM, Java and Python so I was looking for some toy project to learn it.

For a while I couldn’t find a project that was interesting to me and also matched the strengths of Erlang at some point I decided that I would do a small calculator in Erlang, you can see the first commit here and the full project here.

At first I was doing all the eval stuff myself but pretty quickly I added support to compile the expression to an Erlang module with a function. The next commit added function support and then I realized there was a programming language there, you can read the rest of the commits to see how it morphed into one.

At that point the only other beam language other than Erlang was Reia. I wasn’t planning anything in particular with my powerful calculator/language hybrid, but at some point people from Erlang Factory asked me if I wanted to give a talk about my language and of course I said yes, then I got a dose of impostor syndrome, so I started the project from scratch to do a proper programming language and I decided to support every feature that Erlang supports and not much more. At that point the project changed from a toy to an actual programming language.

After my talk and some initial excitement things got quiet. I just had got my Engineers degree and had a new job so development stopped for a while, then Elixir appeared and got much more attention, so I thought “OK, someone got it right, I will just stop pushing efene” and some years passed. But then looking into Elixir I saw that the Elixir ideas weren’t exactly the ideas of efene and I decided to rewrite it to try to fill the niche of “just a different syntax for Erlang, reuse as much as possible from the Erlang ecosystem, unified tooling and documentation as the core of the project”. The language has been complete for a while now. I’m just working on documentation, rebar3 plugins andwaiting for some of the surrounding tools to mature to avoid having to redo the documentation (mainly rebar3 and cowboy 2).

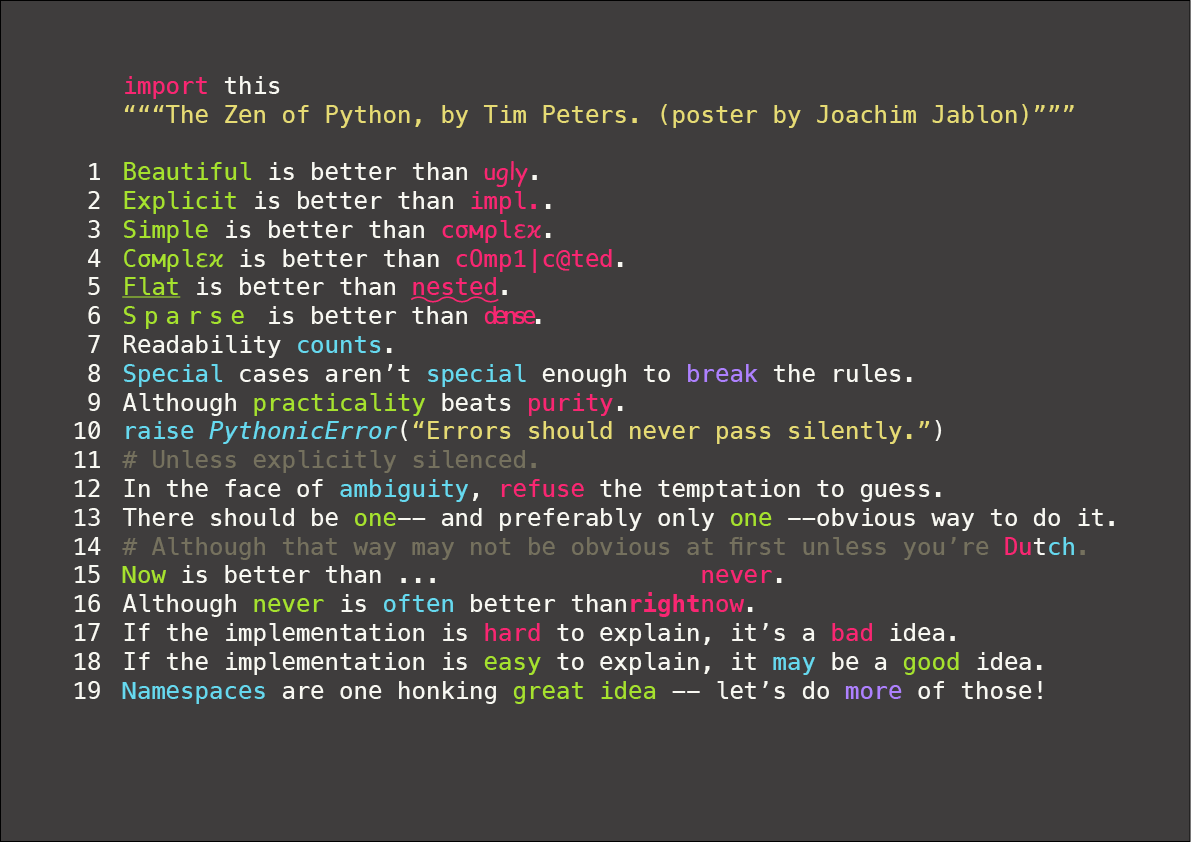

Why do you embrace the Zen of Python?

Python was the first language I enjoyed coding in before I coded in C, C++, ASM and Java, but just because it was what I knew or they provided something I needed. With Python it was the first time I said “I’m a Python programmer” and not “I’m a programmer”, also the Python Argentina community helped a lot witht hat.

Python has this attitude of simplicity and community that I like and instead of coming up with an “ad hoc, informally-specified, bug-ridden, slow implementation of half of the python zen” I decided just to copy it.

David Nolen summarized it well the other day:

That’s why efene is a mixture of what I like about the languages, communities and philosophies of Python, Javascript and Erlang, don’t expect a lot of novelty in efene, just a remix of what’s there :).

Could you show to us a short and good example of an efene program?

I can’t think of a particularly short snippet of code that will show you all the interesting bits of efene, mainly because there are no clever parts to efene, the idea is to be regular, simple, explicit and readable.

This means it doesn’t try to win a codegolf competition, or some clever language trick.

But I think you can take a look at this project which is a client for an API that supports REST, Web Sockets, Server Sent Events and COMET and then starts some clients that send some pseudo-random stuff to test the server:

If your reaction is “I understand this and this is boring”, then I would be happy :), of course knowing some Erlang will help the understanding since efene semantics and patterns are the same as Erlang’s.

Which are the biggest advantages of coding in a language that runs on top of the Erlang VM (BEAM)?

The semantics of the VM are really thought out and really simple to learn.

The stability and scalability of the platform is great and there’s a lot of people that have worked on really hard problems for a long time on top of the Erlang VM, this means you can get really good advice and help from them.

One thing I really like and I don’t think is mentioned that much is the level of runtime introspection and visibility the VM has, and the tooling that is build and can be built around it is great.

What difficulties did you find in implementing efene?

Learning the limits of the parser and what syntax is valid an unambiguous, learning to avoid introducing crazy ideas into the language because syntax and semantics are always tricky and you don’t want to have a “WAT” language.

Also learning about Erlang and its VM while doing it.

But to sum it up, it ended up not being as difficult as I thought it will be, it just requires persistence and some hammock-driven development ;)

Do you have any recommendation for those of us that did not implemented any language yet?

Learn about lexing and parsing, then build a calculator using S-Expressions (Lisp-like) or reverse-polish syntax (Forth-like).

Start it as an interpreter, copy the semantics from a simple language you already know, coming up with good semantics is hard, don’t try to invent them the first time.

Then ride on top of a language you know, either transpile to that language or compile to bytecode or some intermediate representation.

Try to reuse as much of the tooling from the other language as possible (AST from Erlang, AST from Python or similar), this will allow you to reuse all the tooling and code built around those representations.

Read about Lisps and Forth. Implement a simple Lisp (Scheme) or Forth.

Once you learn to lex and parse you can think syntax for languages and try to parse them.

What is the match expression and why did you introduce it?

At the core of efene rewrite was the concept of “Everything revolves around 4 main things, pattern matching, functions, guards and data”, pattern matching is done when using the equal sign (=), on the argument list of a function definition and on other Erlang expressions. I wanted to unify the pattern matching under a single syntax and reuse it everywhere, that’s where the “case clauses” came to be.

If you haven’t look at efene yet, the shape of efene expressions is something like:

<keyword> [<expr-args>]

<case-clauses>

[else: <body>]

endA case-clause has this shape:

case <case-args> [when <guards>]: <body>For example try/catch:

try

<body>

catch

<case-clauses>

[else: <body>]

[after <body>]

endReceive:

receive

<case-clauses>

[else: <body>]

[after <after-expr>: <body>]

endFunctions:

fn [<name>]

<case-clauses>

[else: <body>]

endYou should see a pattern there, since the case keyword was already taken and it’s what Erlang use for what “match” does in efene I had to look for a new keyword.

One thing I like about python is this concept of “executable pseudocode”, I like the fact that if you read Python code aloud it sounds like what it does, so I thought “what am I doing here”, “I’m matching and expression against cases”, in imperative it would be “match A [against] case B, case C, else … end” and that’s how I ended up with match.

Why did you introduce a for expression?

The initial idea for efene was to be familiar for people coming from “algol-like” or “mainstream” languages, so they can focus on learning what’s interesting about Erlang which are the semantics and the abstractions and avoid learning a new syntax on the way to epiphany.

Since list comprehensions aren’t available in many of those languages but “for” is, I decided to implement list comprehensions as a more familiar construct but in fact it does the same.

What is the arrow operator and why did you add it?

First a quick introduction for people unfamiliar with efene or the arrow operator.

There’s this thing in Erlang where if you want to apply a sequence of operations to a list you have to create a new binding for each intermediate result:

MyList = create_list(),

MyList1 = op1(MyList),

MyList2 = op2(MyList1),

MyList3 = op3(MyList2),

MyList4 = op4(MyList3).Then if you want to reorder or remove some of the operations you have to rearrange the names to fit.

The idea of the arrow operator is to help with that, it’s a compile operation, this means that if you write:

MyList = create_list() -> op1() -> op2() -> op3() -> op4()It will compile to:

MyList = op4(op3(op2(op1(create_list))))The thing is that the Erlang libraries don’t have a standard position for the thing you are operating on like in other languages where it tends to be the first argument, inspired by Clojure (http://clojuredocs.org/clojure.core/-%3E and http://clojuredocs.org/clojure.core/-%3E%3E)

I created two variants:

“->” adds the result of evaluating the expression on the left as first argument on the function call on the right

“->>” adds the result of evaluating the expression on the left as last argument on the function call on the right

But thinking about symmetry and other common idiom in Erlang and other functional languages which is higher order functions (passing functions as arguments to other functions) I decided to create the reverse of those but with a more restricted use.

“<-” adds the case clauses on the right as an anonymous function as last argument on the function call on the left.

“<<-” adds the case clauses on the right as an anonymous function as first argument on the function call on the left.

You can see it says “case clauses” and not “anonymous function”, this is because you don’t have to write the *fn* keyword, it gives this expression a DSL taste that I like, for example:

lists.map(Things) <<-

case 0: zero

case A when A % 2 is 0: even

else odd

endGoing back to the restricted uses of the right-to-left arrows it’s because since code reads from left to right, putting something on the right that is just a value doesn’t help readability hence I decided not to support it.

I just saw that you are creating a new language for the BEAM called interfix. What is it?

As I said above, efene is a language that doesn’t try to come up with anythingnew. This led me to avoid doing experiments on efene itself, but I still wanted to do those experiments somewhere else.

With time the number of ideas for crazy languages I had grew and condensed to a point I thought I had a nice little language. Then coming back from a conference I had a lot of dead time on airports and no internet so I decided to give it a try.

After I landed, the language was growing and all the ideas I had didn’t seem to have any problems so I kept growing it quite fast and for the last days it’s almost a complete language (in the sense that it can do everything Erlang can do).

At this point I’m finishing adding the remaining features and when everything is there and I know everything fits I will move to cleaning the code and adding some tooling and docs around it for people that want to play with a more “experimental” language.

I say experimental in the sense that it has some crazy ideas in it but not experimental in that it will crash, break backward compatibility or compile the code to wrong bytecode.

You wrote the Little Riak Core Book and you gave a talk called From 0 to a working distributed system with riak_core. Could you explain what riak core is and why it can be useful for those of us who implement distributed systems?

Riak Core is the foundation of Riak KV and other Basho projects, it’s the generic and reusable part of a “dynamo style” distributed system, it provides some abstractions and utilities to build multi-node, master-less distributed systems.

In a Riak Core based application you build your system by implemented interfaces to handle the work your application does inside virtual nodes (vnodes) that live inside a ring of vnodes, the work is done by routing commands consistently to those vnodes by hashing a key that you specify.

It also provides ways to run a command in more than one vnode and compare the results, grow or shrink the cluster without downtime, migrate vnodes between physical nodes, authentication/authorization and a metadata system to hold information about the cluster and your application in a distributed manner.

This frees you from having to implement all this building blocks so you can focus on what actually makes your application different and building upon a tested and production ready foundation.

While reading your blog I could see that you have used Scala and Clojure apart from Erlang. What has been your experience with Scala and Clojure? What advantages and disadvantages did you find when comparing Scala, Clojure and Erlang?

The experience with the 3 programming languages has been really good, I’ve built similar systems with those programming languages (a kind of pub/sub system with persistence), the reason I moved this backend initially from Scala (lift+akka) to Clojure (immutant) was because the system handled lot of semi-structured data both from the frontend and the backend and I was using a lot of time putting that data into “rigid” types to serialize it to json again

after some operations, and each time the shape of the data evolved on the frontend or the storage I had to go and change those types in a backward compatible manner and it was getting really tiring since the backend was really simple in what it actually did.

So I decided to move to Clojure and it resulted in a huge reduction on code but after the code evolved I saw myself implementing this pub/sub like system by hand with low level tools like agents, atoms and promises copying the Erlang “patterns”, at this point some customers were asking about scalability and clustering, so I decided to do a prototype using riak_core and after some coding we tried at a new project and since we could improve it fast and it was working quite nice we decided to adopt it as our default backend.

I’m still using scala for Spark jobs, I use clojure for internal tools and internal frontends with clojurescript but the backend now is Erlang.

I just want to clarify that our backend is quite simple in what it does so moving between languages in the backend is not a big deal, the bulk of what we do is in our frontend code.