Interview with Brad Chamberlain about a productive parallel programming language called Chapel

As you might know, I am a big fan of concurrency, parallelism and distribution but I know almost nothing about high performance computing…

As you might know, I am a big fan of concurrency, parallelism and distribution but I know almost nothing about high performance computing (HPC) so I decided to get out from my comfort area. This time I’ve interviewed Brad Chamberlain about Chapel, a productive parallel programming language.

What problems does Chapel solve? Who is the ideal user of Chapel?

Chapel supports scalable parallel programming in a portable way: programs developed on a user’s multicore laptop can be run on commodity clusters, the cloud, and supercomputers from Cray or other vendors. Chapel is also designed to vastly improve the productivity of performance-oriented programming, whether serial or parallel. As such, it supports programs with Python-like clarity while retaining the performance of lower-level approaches to programming like C, C++, Fortran, MPI, and OpenMP (the de facto standards for high-performance parallel programming).

Ideal Chapel users include Python programmers who are interested in parallel or performance-oriented programming as well as parallel programmers who are fed up with conventional approaches.

Were there any other previous languages that tried to solve the same issue?

Definitely. There’s a long list of failed attempts at developing scalable parallel programming languages, and skeptics like to remind you of them all the time: “If all of these languages have failed, how will you ever succeed?” In designing Chapel, we spent a lot of time reviewing other parallel languages to learn from their mistakes. Historically, I’d say that most parallel languages have failed for one of two reasons: Many were too high-level, limiting what an expert programmer could explicitly control while requiring a lot from their compilers. Others were lower-level, but as a result didn’t provide sufficient appeal over existing approaches like MPI.

Our response to this tension was to design a language using what we refer to as a multiresolution philosophy: Chapel supports higher-level features like parallel loops and distributed arrays for productivity and ease-of-use. Yet, it also supports lower-level features that give programmers more explicit control over the system. Notably, the high-level features are implemented in terms of the lower-level features within Chapel itself. This provides programmers with the ability to extend the language by creating their own abstractions. For example, an advanced Chapel user can implement new work-scheduling policies for their parallel loops, or new distributions or memory layouts for their arrays.

In my opinion, many scalable parallel language attempts have also failed to gain traction because they’ve been insufficiently general-purpose. Once programmers have a capability, they tend to be reluctant to give it up. This lack of generality often stems from the fact that most efforts have been undertaken by academic groups who need to pick their battles in order to publish papers and graduate students. With Chapel, we’ve created a language whose capabilities exceed C or Fortran with MPI and OpenMP, yet in a language that strives to be as attractive to read and write as Python.

It’s obviously very difficult for any new programming language to succeed, yet that’s no reason to avoid pursuing them — particularly when existing languages have major capability gaps. In our case, we believe that parallelism and locality are first-class programming concerns — not just in High-Performance Computing (HPC) where they make or break a program’s ability to scale well, but also in mainstream programming now that multicore processors and accelerators are pervasive. That said, parallelism and locality have traditionally been afterthoughts in language design. So rather than being paralyzed by the challenges of language adoption, we’re striving to fill that gap. And happily, users seem to be excited by our efforts.

In some ways, don’t OpenMP, MPI, and CUDA solve the same problem?

OpenMP, MPI, and CUDA are the de facto standards for HPC programmers today when targeting multicore processors, distributed memory systems, and (NVIDIA) GPUs, respectively. In that sense, Chapel is targeting a similar problem space as they are. However, they’re not considered very productive approaches and are great illustrations of my claim that parallelism and locality are traditionally afterthoughts in language design: they’re implemented using pragmas, libraries, and language extensions rather than first-class syntax and semantics. As a result, they feel like they’re “tacked on” rather than a core part of the language. This hurts not just their ease-of-use but also their ability to be optimized by compilers.

These approaches also tend to be very specific to a given type of parallelism in the system architecture: If you’ve written an OpenMP program and now want to run it at scale on a cluster or a Cray, you’ll have to rewrite it in something like MPI, which requires learning a completely different set of features and abstractions. In contrast, Chapel is designed to support parallel programming across these diverse types of parallel hardware with a single, unified set of features for expressing parallelism and locality.

To their immense credit, OpenMP, CUDA, and (especially) MPI have been responsible for the vast majority of scientific advances in high-performance computing over the past several decades. And if you program in these notations and are happy with them, Chapel may not be for you. Yet, just as early computational results were obtained using assembly language before giving way to more modern and portable approaches like Fortran, C, C++, Java, and eventually Python, we think parallel computing is overdue for a similar leap in evolution: from lower-level, detail-oriented approaches to higher-level ones that improve productivity and portability. As such, Chapel strives to empower the millions of desktop-only programmers to use distributed parallel computers for the first time, while also making existing parallel programmers even more effective.

What does Chapel do differently / better?

A characteristic shared by most general-purpose approaches to scalable parallel programming — including MPI, SHMEM, UPC, and Fortran 2008’s co-arrays — is that they express parallelism using the Single Program, Multiple Data (SPMD) programming model. The basic idea is that the user writes their program with the understanding that when it is run, multiple copies of ‘main()’ will execute simultaneously and cooperatively across a number of processors. This forces parallel programmers to write programs using a local view, in which the code expresses the perspective of a single process out of many: “What subset of the data do I need to allocate? What subset of the iteration space do I need to execute?” While the SPMD approach is sufficient for many computations, it’s also very different from traditional programming where one copy of ‘main()’ executes and all computation proceeds from that point. This requires programmers to think differently, to manage lots of bookkeeping details, and even to launch their programs differently. It also means that in order to get finer-grain parallelism, they need to mix in some other parallel programming model like POSIX threads, OpenMP, or CUDA.

In stark contrast, Chapel supports what we call a global view of programming, in which a single task runs ‘main()’ and then any additional parallelism is created as features that introduce tasks are encountered. Similarly, computation and data are distributed across compute nodes when features that control locality are encountered. This permits scalable parallel programming to be far more intuitive and similar to conventional desktop programming, making it accessible to the millions of developers who might never get around to learning MPI. At the same time, Chapel’s global view also supports SPMD programming for computations or users that require it, so nothing is lost.

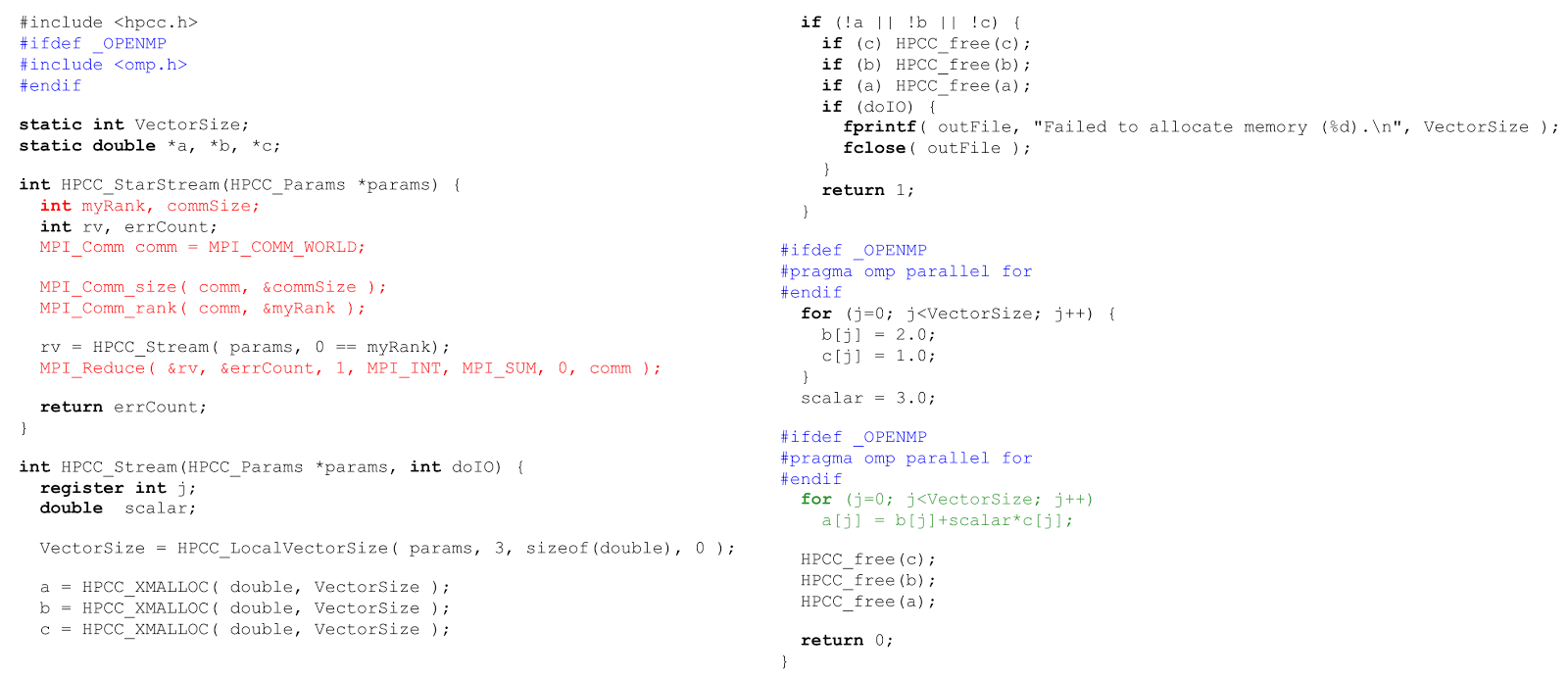

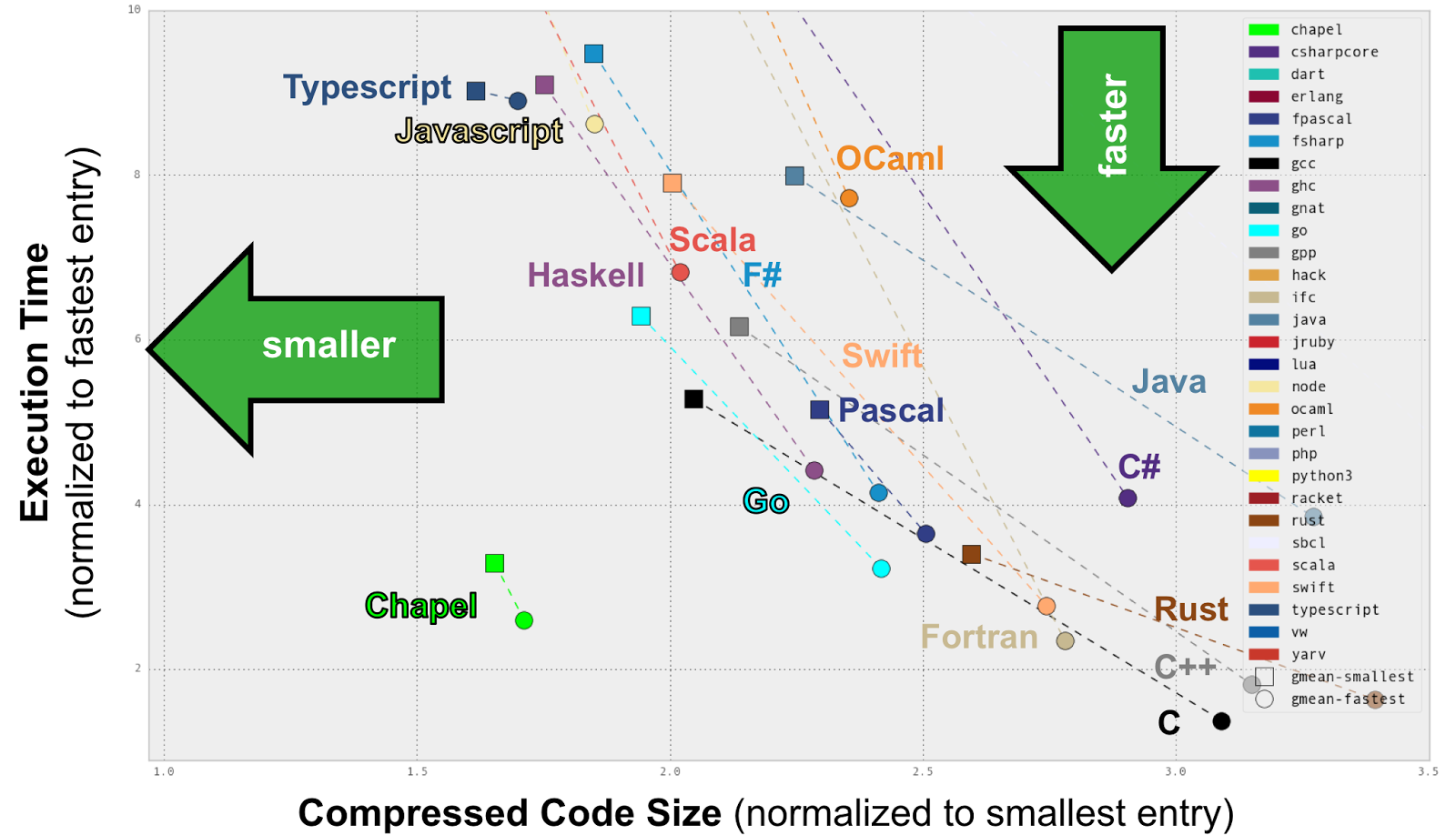

As an illustration of Chapel’s advantages, consider the STREAM Triad benchmark which multiplies a vector by a scalar, adds it to a second vector, and assigns it to a third. In Chapel, this can be written in a way that will use all the cores of all the system’s compute nodes as follows:

use BlockDist, HPCCProblemSize;config type elemType = real;

config const m = computeProblemSize(numArrays=3, elemType),

alpha = 3.0;proc main() {

const ProblemSpace = {1..m} dmapped Block(boundingBox={1..m});

var A, B, C: [ProblemSpace] elemType; B = 2.0;

C = 1.0; A = B + alpha * C;

}In contrast, doing the same thing in C + MPI + OpenMP results in computation like the following, due to the SPMD programming model as well as the lower-level notations (MPI-oriented code is in red, OpenMP in blue):

Performance-wise, how does Chapel compare to languages like C, C++, Go, Rust?

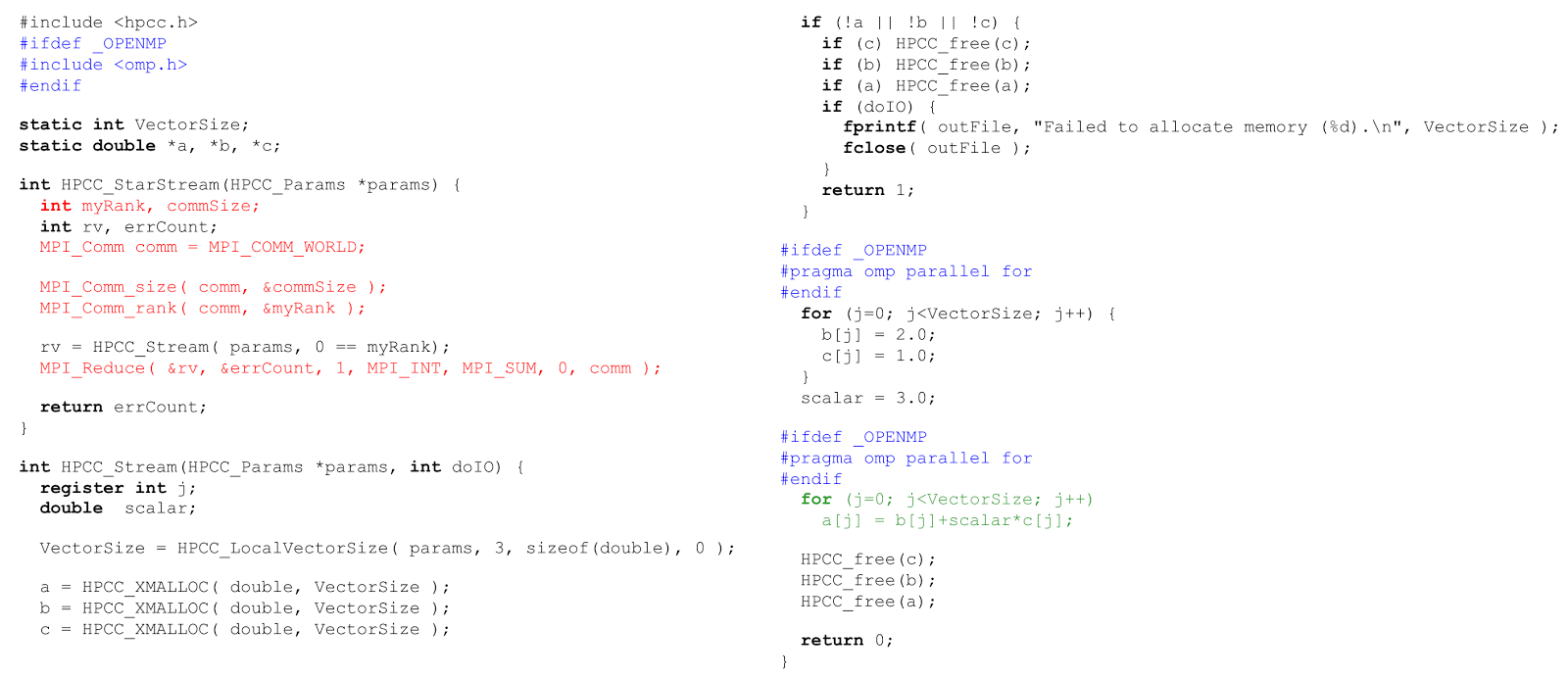

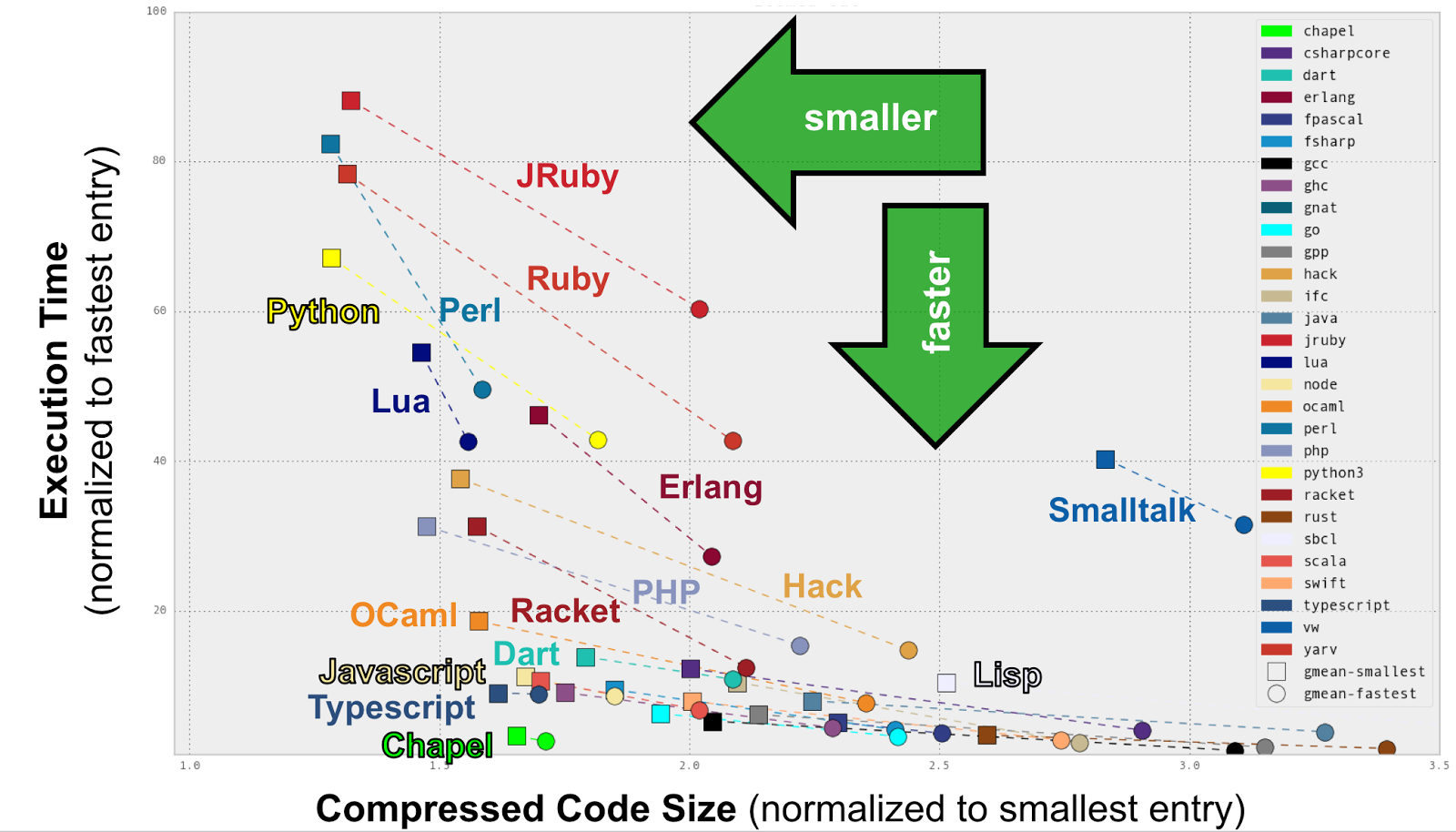

Today, Chapel programs tend to perform competitively with hand-coded C and C++. I’m not aware of any detailed performance comparisons with Go and Rust, though in the Computer Language Benchmarks Game (CLBG) we’re currently ranked as being a bit faster than Go and a bit slower than Rust. That said, there are specific CLBG benchmarks where any of these five languages win or lose, and many of the fastest entries take a far more heroic and painstaking approach than the Chapel versions.

Since we care about code clarity, we tend to graph the Computer Language Benchmark Game results on scatter plots showing normalized execution times versus code compactness (as a proxy metric for clarity). In such views, Chapel tends to fall in a very unique position, being competitive in speed with the fastest languages while also nearly as compact as scripting languages. The following two plots illustrate this (the right graph zooms in on the fastest entries for readability):

Why did you implement Chapel using LLVM?

In all honesty, one of my biggest regrets in the project today is that we didn’t implement Chapel using LLVM from day one. When our project started, LLVM was still in its infancy, and there was no reason to believe that it would become the foundational technology that it is today. As a result, our initial compiler approach (which remains the default today) was to compile Chapel down to C which is then compiled by the back-end C compiler of your choice. This approach treats C as a portable assembly language and has worked reasonably well for us over time. However, it is also unfortunate because the Chapel compiler may have semantic information which is challenging or impossible to convey through C to the back-end compiler.

In contrast, Chapel’s LLVM back-end permits us to translate Chapel directly to LLVM’s Internal Representation (IR), giving us greater semantic control plus the possibility of adding Chapel-specific extensions. Since LLVM is a popular compiler framework, using it lets us leverage developer familiarity, not to mention open-source packages. One such example is Simon Moll’s Region Vectorizer for LLVM, developed at Saarland University. We’ve found that it tends to generate better vector performance for Chapel programs than conventional C back-end compilers. But even more importantly, LLVM gives us a single, portable back-end that saves us the trouble of wrestling with the quirks and bugs that are present across the wide diversity of back-end C compiler versions that we attempt to support today. In 2018, we hope to make LLVM our default back-end for these reasons.

What is GASNet? Why do you use it in Chapel?

GASNet is an open-source library for portable inter-process communication developed by Berkeley Labs / UC Berkeley. Its communication primitives include active messages and one-sided puts to (or gets from) the memory of a remote process. The GASNet team maps these calls down to the native Remote Direct Memory Access (RDMA) capabilities of various networks while also supporting fallback implementations over UDP or MPI for portability.

These primitives are precisely what a language like Chapel needs to compile to distributed memory systems: Active messages are the natural way to implement Chapel’s on-clauses which are used to migrate tasks from one compute node to another. Similarly, writing/reading a variable back on the originating locale maps naturally to one-sided puts/gets since only one process will know when such communications are required. As a result, GASNet gives us a portable way to run Chapel on virtually any distributed system. It’s also one of the best engineered and maintained open-source packages we’ve worked with, and the development team is incredibly responsive to questions and issues.

How do you manage errors? If a long-running computation in multiple nodes crashes in one node, how do you recover the work done or re-execute it without having to re-run everything?

For user-level errors within the program itself, Chapel supports the ability to throw and catch errors using a low-overhead approach that was inspired by Swift’s error-handling model. This is a relatively new feature set within Chapel, and it rounds out our core capabilities nicely.

That said, your question seems more oriented toward catastrophic errors that may be outside of the programmer’s control, such as having one of their compute nodes fail. Today, Chapel doesn’t handle such cases gracefully, which arguably reflects our HPC heritage. Runtime libraries and system software for HPC have a long tradition of tearing down jobs when fatal errors occur, and Chapel inherits this behavior to some extent. Resiliency is a growing concern within the HPC community as our system scales grow, and we have some ideas for improving Chapel’s ability to cope with such events. Similar features could also be attractive to users from cloud computing environments who are accustomed to elasticity in their environment. That said, we have not yet had the opportunity to pursue these ideas, so they remain an area of potential future research or collaboration.

Is there any way to trace what a live system is currently doing?

We haven’t developed any Chapel-specific tools for tracing or visualizing Chapel executions in real-time. That said, third-party tools can be used with Chapel as with any other C program. We do have a tool named chplvis, developed by Professor Phil Nelson of Western Washington University, which supports visualizing the communication and tasking events logged by a Chapel program. This permits a user to visually inspect a Chapel program’s execution to find possible sources of overhead, but it is strictly a post-mortem tool at present.

Are you aware of anybody using Chapel in the AI/Machine Learning world?

We’ve definitely seen an uptick in interest from AI programmers in recent years as the field has become more prevalent, both in HPC and in general. Our most prominent user in this space at present is Brian Dolan, who is the Chief Scientist and Co-Founder of Deep 6 AI, a start-up that is accelerating the matching of medical patients to clinical trials. After being disappointed by programming solutions that didn’t live up to their hype, Brian was drawn to Chapel last summer due to its ability to support programs with Python-like clarity, combined with the promise of supporting performance and scalability like C or Fortran with MPI. Half a year later, he’s become one of our most active and vocal users.