There’s more to life than HTTP: VerneMQ a high-performance and distributed MQTT broker

At LambdaClass and our blog This is not a Monad tutorial we are a big fans of exploring new topics, different operating systems, platforms…

At LambdaClass and our blog This is not a Monad tutorial we are a big fans of exploring new topics, different operating systems, platforms, languages and libraries/frameworks. We have been talking in our company about exploring new subjects like protocols.

There is a whole generation of developers that has only worked with HTTP, ReST and JSON. While a partial improvement over previous technologies, it has created a protocol monoculture. There are situations where other protocols are better suited but many of the young bloods don’t even know they exist.

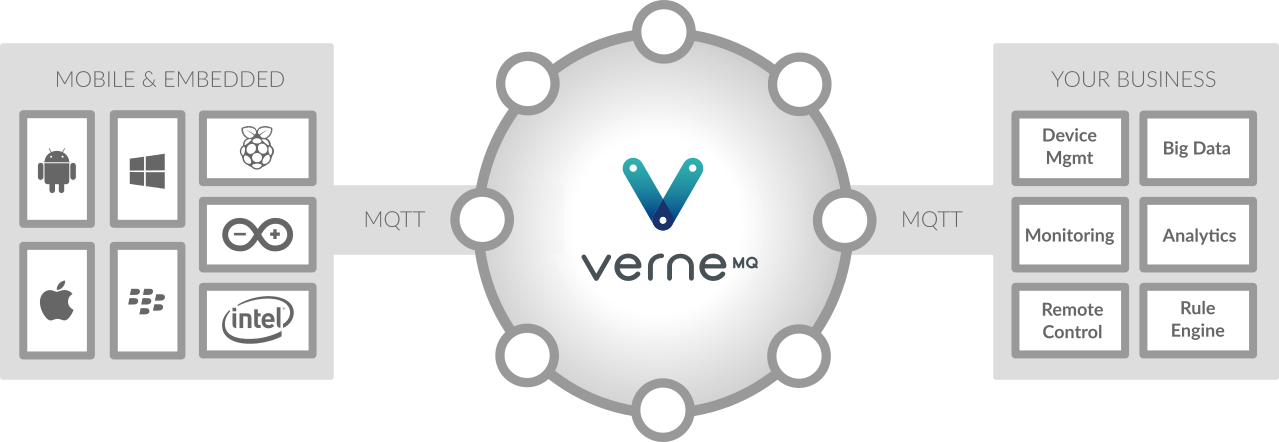

MQTT is the first protocol we want to dive into. For us VerneMQ (https://vernemq.com/ and https://github.com/erlio/vernemq) is one of the best MQTT brokers implementations we know and it is familiar to us since it is implemented in Erlang. The questions were answered by André Fatton, André Graf and Lars Hesel Christensen.

What is MQTT?

MQTT was developed by Andy Stanford-Clarke (IBM) and Arlen Nipper (Cirrus Link) in 1999 as a light-weight protocol efficient in terms of bandwidth and resource usage. In fact one of the original use cases was to send telemetry back from oil-pipelines in remote areas where transmitting data is expensive and service windows are far between. The defining feature of MQTT is that it is a dynamic pub/sub type paradigm where clients need to actively subscribe to a topic to receive messages published to it, thus decoupling producers and consumers completely. MQTT also supports various quality of service levels as well as persisted sessions and a few other handy things.

What is VerneMQ?

VerneMQ is an open source (Apache License version 2) MQTT broker supporting the MQTT 3.1.1 standard as well as MQTT 5.0 (though, to be fair MQTT 5.0 support has not yet been merged to master at the time of writing, but should be within a few days). Besides being just another MQTT broker, VerneMQ was built from the start to be a distributed MQTT broker with high scalability in mind.

Why would somebody use MQTT instead of HTTP 2 or WebSocket?

MQTT, HTTP/2 and WebSockets all have their strengths and weaknesses. HTTP is a request/reply type protocol, while MQTT is a publish/subscribe type protocol. So if all you really need is request/reply then MQTT might not be the right choice for the use case. But if the messaging patterns are more complex such as fan-in and fan-out and none or a small part is request/reply, then MQTT might be an appropriate choice. What MQTT brings to the table is decoupling of the producers and consumers and all the flexibility that comes with that as well as a well defined routing mechanism based on subscriptions with wildcards. In an HTTP or WebSocket context one would have to build a custom routing scheme, which may of course be better suited for the job than something general as MQTT. On the other hand if the desired features are supported by MQTT, then MQTT has a huge advantage in that it is an open (and royalty free) standard and high quality client libraries are available in pretty much any programming language one could imagine.

Does it have an overlap with other protocols like AMQP (implemented by RabbitMQ for example)?

Yes, essentially both AMQP (speaking for the 0.9.1 version) and MQTT implement a publish/subscribe messaging pattern. Both protocols rely on intermediate queuing/store-and-forward techniques to reduce or eliminate message loss in case a client loses the connection to the broker. The main conceptual difference is that in MQTT one client (identified by a ‘unique’ client id), has one TCP connection to the broker and only a single “queue”. As a consequence, even if a client has multiple subscriptions all messages end up in the same queue. In contrast, with AMQP a queue is a resource on the broker and is decoupled from the client, multiple clients can consume the same queue e.g. for load balancing purposes. So a client can create many queues and decide if and when to consume messages. Moreover, a AMQP connection, which is just a TCP connection, is multiplexed via logical channels, enabling the development of highly performant consumers and publishers.

Why did you decide to implement another MQTT broker?

We stumbled upon the MQTT protocol while working for a customer on a IoT project that heavily used RabbitMQ and AMQP. Although AMQP has been a requirement by the customer we soon figured out that AMQP (and RabbitMQ) might not be the silver bullet for every messaging use case and started to look out for a better IoT protocol. We discovered MQTT and found it a very interesting addition to the other protocols that were widely in use back then and still are today. Especially the small protocol overhead and the focus on small devices (embedded and mobile) instead of big application servers teased us to take the protocol a bit further. Even more so because at that time no scalable and clusterable MQTT broker was around, MQTT was always added as an addition to a ‘main’ protocol like it was done in RabbitMQ or Apache Apollo. We generally disliked the idea of such a ‘multi-protocol’ capability. For example an AMQP broker was traditionally serving a few hundreds to a few thousands of publishers and subscribers with a high message throughput so you build a broker around such scalability and performance requirements. However a traditional MQTT case is the exact opposite, you have ‘a lot’ (a few thousands to a few hundred thousands, to millions) of clients each one only publishing very rarely very small messages. Combining the two protocols in a single software, reusing shared functionality, and still being able to match all the requirements from both worlds seemed like a tough job, too tough for us, and back then no broker known to us did that successfully and we think still no one does today.

Is there anything you dislike about MQTT or that needs an improvement?

Sure, while MQTT v3.1.1 is a great protocol, there are a number of limitations. An example is the lack of negative acknowledgements. Take for example a client attempting to publish to a topic where it’s not authorized to do so: the only action allowed according to the spec is to simply disconnect the client with no way telling it why, which is a bit heavy handed. Another example is that there is no way to add meta information to MQTT payloads such as a content type or decoding schemes etc. The only way to deal with this is to decide on an a priori scheme and encode this information into the payloads themselves. A common workaround is to embed the payload into a thin wrapper which contain such information — but it’s always ad-hoc in every system out there.

Fortunately the OASIS consortium has been working with feedback from the community and carefully used these to develop the next version of the MQTT protocol, MQTT protocol version 5.0. This version basically addresses the issues mentioned above by incorporating them into the protocol, providing a standard way of doing things. We’re really excited about the new protocol version, so we even wrote a bit about it in Is MQTT 5 worth the trouble?.

Why did you choose Erlang to implement it?

We chose Erlang because it was the right tool for the job. Erlang was designed to support highly concurrent and highly available (through fault tolerance) systems which fits exactly for a project like VerneMQ. It was also important that the concurrency model was a first class concept and the units of concurrency can’t block each other if one happens to run for a long time as that would be detrimental when building a low latency system. There are a lot of other features which make Erlang a great tool to work with, the way supervision trees makes writing defensive code unnecessary is an important one as one only writes code to handle only the cases the problem domain requires. This makes the code generally brief and concise. The core of VerneMQ including tests is about 30K lines of Erlang code which we think is quite remarkable.

After implementing it, do you think you made the right call using Erlang to implement VerneMQ?

Yes, absolutely. To build the best possible product Erlang was definitely the right choice. We still think it is one of the best options out there, today there are other interesting options though.To us an obvious one is Elixir, but another, albeit more exotic (we know this might sound ironic coming from a Erlang devs) option would be something like Pony which is an extremely interesting language since it eliminates a lot of nasty error classes (deadlocks, data-races, exceptions etc) via the type system and the guys over at Wallaroo Labs are building some pretty amazing stuff with it.

We really love Erlang, but we’re also being realistic that if there’s a better technology or the use case doesn’t require or benefit from the featureset we’re completely open to use other tools for the job.

How do you retain messages and replicate subscription data?

Great question! A retained message in MQTT is a message which is stored on the broker using a topic as the key and whenever a client subscribes to that particular topic the broker delivers a copy of the message. Since VerneMQ is a distributed broker we need to replicate retained messages and for this we currently use an implementation of the Plumtree protocol which was initially implemented for the now defunct Basho Technologies’ distributed database Riak. Later this implementation was factored out into its own repository and we maintain our own fork with a bunch of tweaks. Note, that the replication mechanism in VerneMQ is eventually consistent as this is much easier to scale as no distributed locking is required.

Besides the retained messages VerneMQ also needs to distribute client session state such as subscription information so each VerneMQ node is able to route the published messages across the cluster.

This is all currently handled using Plumtree and Plumtree is doing a great job of it. That said, Plumtree uses relatively many resources when syncing nodes (it uses Merkle trees under the hood) and using plain dotted vector clocks means that deleting things require cluster wide synchronization as it is not possible to distinguish between something which was deleted and something which is just missing. To address this we’re working on implementing a new replication mechanism called Server Wide Clocks which combines vector clocks per key-value pair with a node-clock for each participating node, making it possible to establish a global history and thus discard events observed by all members. This makes deletions a special case of the general history trimming process. Furthermore replications with SWC is cheaper than in Plumtree as no Merkle trees are needed and there’s a much smaller overhead per key-value pair on the wire while replicating the state.

What load can VerneMQ manage? Do you have a concrete example (number of nodes, number of connections per node, throughput, latency, etc)?

This is a difficult question we can’t give a straight answer for. The main reason for this is that the scenarios, use cases, and deployment environments are very different. E.g. we know people deploying a VerneMQ cluster on a couple of Raspberry PIs, and others deploying a large cluster on Kubernetes. Unfortunately many vendors started to publish benchmarks that are hard if not impossible to reproduce, mainly for marketing purposes. While we don’t exclude doing this in the future, we’d prefer a more scientific approach. For now, we develop and publish benchmarking tools, so everyone can run a benchmark scenario matching their own use case and see how VerneMQ and also other brokers perform. Moreover those benchmarking tools will simplify the reproducibility once we publish any sort of benchmarks.

That said, we saw several interesting setups on the road of course. Some were more successful than others. E.g. someone deployed a VerneMQ cluster of 80 nodes over multiple sites and managed to connect around 5 millions clients. Obviously they run into multiple problems with such a setup, and required our assistance to design a better architecture. Right now we’re helping a customer to scale a MQTT application to 10+ millions concurrent clients, we’ll see how this ends, but we’re quite confident that we come up with a good VerneMQ setup for this case.

How do you test VerneMQ?

About 25% of the code is test code — of course this doesn’t mean much, but we believe our test suites are pretty thorough. Of course they can always be better, and we routinely add new tests whenever a bug is discovered or a new feature is added. Almost all of our tests are written as Common Test suites as it’s a really fantastic framework which makes it easy to do both unit and integration tests. We do have a few tests written as EUnit tests but almost all new tests are written using Common Test. We’re great fans of property based testing, but so far we haven’t invested enough into making a proper property based test suite. It’s something we’d love to do at some point, though.

What was the most challenging part of VerneMQ to design and build?

In Joe Armstrong’s saying “Make it work, make it beautiful, make it fast” the initial “Make it work” wasn’t too challenging, most of the engineering problems were already solved and it was about combining multiple approaches. We borrowed a lot from the way Basho was building and packaging the Riak database as well as the previously mentioned Plumtree. Moreover the initial topic trie routing algorithm was fully taken from the RabbitMQ MQTT plugin. Also the early decision to use LevelDB for disk persistence simplified a lot in the beginning. So it wouldn’t be fair to say that that part was very challenging, especially at the beginning, where we just wanted it to work. Moreover the ‘supposed-to-be-challenging’-part was already solved by Erlang and its distributed nature. However, back then it was challenging to stay focussed on what VerneMQ should become and not adding every possible feature in a half-baked way. So we focussed on a solid plugin system instead of providing everything out of the box right from day one. In retrospective the engineering of the plugin system was actually quite challenging.

These days the implementation of the SWC challenges us as the distributed algorithm is quite complex and we couldn’t just use an existing library for that. Moreover the implementation and integration of the MQTT 5 further challenges also our plugin system.

What’s ahead for VerneMQ?

First of all we’re going to get the MQTT 5 support merged into the master branch, and then work with the community and our uses to squash the inevitable bugs and make it better. Parallel to that we’re working on getting the improved replication mechanism (SWC) in place which will be available in VerneMQ 2.0, but may also be made available in the 1.x series as an opt-in feature. Besides this we’re working on improving the entire experience around containerization (Kubernetes, etc), clustering, discoverability and the tooling around that. So lots of interesting stuff going on.

What do you recommend to do or read (books, courses, RFCs, codebases, exercises) for young devs that want to start working with distributed systems?

This is a really good question but also a really hard one to give a good answer to. When we studied computer science most of the results on distributed systems made so many crazy assumptions that they were more or less unusable to build actual systems from. So for a practitioner it was a disappointing experience, but it did give us a good understanding of what the challenges of distributed computing are. When starting out from scratch with distributed computing this is probably a good place to start: Learning about the basics such as the Fallacies of distributed computing and some of the impossibility results such as the CAP theorem. To really learn about and understand distributed systems it’s important to work and play with them and for this we of course recommend either Erlang or Elixir as they come with distribution built in so there’s a very low barrier to getting started. Also the actor model of Erlang forces one to start thinking about message passing and building protocols which is really what distributed systems are all about.

To learn anything the best advice usually is to make sure to play and have fun. So go have fun!