What every developer needs to know about elliptic curves

Elliptic curves (EC) have become one of the most useful tools for modern cryptography. They were proposed in the 1980s and became widespread used after 2004. Its main advantage is that it offers smaller key sizes to attain the same level of security of other methods, resulting in smaller storage and transmission requirements. For example, EC cryptography (ECC) needs 256-bit keys to attain the same level of security as a 3000-bit key using RSA (another public-key cryptographic system, born in the late 70s). ECC and RSA work by hiding things inside a certain mathematical structure known as a finite cyclic group (we will explain this soon). The hiding is done rather in plain sight: you could break the system if you could reverse the math trick (spoiler alert: if done properly, it would take you several lifetimes). It is as if you put $1.000.000 inside an unbreakable glass box and anyone could take it if they could break it.

In order to understand these objects and why they work, we need to go backstage and look at the math principles (we won't enter into the hard details or proofs, but rather focus on the concepts or ideas). We will start by explaining finite fields and groups and then jump onto the elliptic curves (over finite fields) and see whether all curves were created equal for crypto purposes.

Finite fields

We know examples of fields from elementary math. The rational, real and complex numbers with the usual notions of sum and multiplication are examples of fields (these are not finite though).

A finite field is a set equipped with two operations, which we will call + and ×. These operations need to have certain properties in order for this to be a field:

- If a and b are in the set, then c=a+b and d=a×b should also be in the set. This is what is mathematically called a closed set under the operations +, ×.

- There is a zero element, 0, such that a+0=a for any a in the set. This element is called the additive identity.

- There is an element, 1, such that 1×a=a for any a in the set. This element is the multiplicative identity.

- If a is in the set, there is an element b, such that a+b=0. We call this element the additive inverse and we usually write it as −a.

- If a is in the set, there is an element c such that a×c=1. This element is called the multiplicative inverse and we write is as a−1.

- The operation is associative, that is, (a×b)×c=a×(b×c).

- There is an identity element, e: e×a=a and a×e=a.

- For every element a in the set, there is an element b in the set such that a×b=e and b×a=e. We denote b=a−1 for simplicity.

Before we can talk about examples of finite fields, we need to introduce the modulo arithmetic.

We learned that given a natural number or zero, a and a non-zero number b, we could write out a in the following way a=q×b+r where q is the quotient and r is the remainder of the division of a/b. This r can take values 0,1,2,...,b−1 We know that if r is zero, then a is a multiple of b. It may not seem new, but this gives us a very useful tool to work with numbers. For example, if b=2 then r=0,1. When it is 0, a is even (it is divisible by 2) and when it is 1, a is odd. A simple way to rephrase this (due to Gauss):

a≡1(mod2)

if a is odd and

a≡0(mod2)

if a is even. We can see that if we sum two odd numbers a1 and a2,

a1+a2≡1+1≡0(mod2)

This shows us that, if we want to know whether a sum is even or not, we can simply sum the remainders of their division by 2 (an application of this is that in order to check divisibility by two, we should only look at the last bit of the binary representation).

Another situation where this arises every day is with time. If we are on Monday at 10 am and we have 36 hours till the deadline of a project, we have to submit everything by Tuesday 10 pm. That is because 12 fits exactly 3 times in 36, leading to Mon-10 pm, Tue-10 am, Tue-10 pm. If we had 39 hours, we jump to Wed-1 am.

An easy way to look at this relation (formally known as congruence modulo p) is that if a≡b(modp), then p divides a−b, or a=k×p+b for an integer k.

More informally, we see that operating (mod p) wraps around the results of certain calculations, giving always numbers in a bounded range by p−1.

We can see that if a1≡b1(modp) and a2≡b2(modp), then a1+a2≡b1+b2(mod p) (if b1+b2>p we can wrap around the result). Similar results apply when using subtraction and multiplication. Division presents some difficulties, but we can change things a little bit and make it work this way: instead of thinking of dividing a÷b we can calculate a×b−1, where b−1 is the multiplicative inverse of b (remember b×b−1=1). Consider p=5, so the elements of the group are 0,1,2,3,4.

We can see that 1 is its own multiplicative inverse, since 1×1=1≡1 (mod5). If we take 2 and 3, then 2×3=6≡1 (mod5) (so 3 is the multiplicative inverse of 2) and 4×4=16≡1 (mod5). The set and the operations defined satisfy the conditions for a field.

We can also define integer powers of field elements in a simple way. If we want to square a number a, it is just doing a×a and take mod p. If we want a cube, we do a×a×a and take mod p. RSA uses exponentiation to perform encryption. It is easy to see that if the exponent is rather large (or the base is very large, or both), numbers get really big. For example, we want to evalute 265536(mod p). When we reach a 1000, we get numbers with over 300 digits and we are still a long way to go. We can do this calculation much simpler realizing that 65536=216 and squaring the number and taking the remainder every time. We end up doing only 16 operations like this, instead of the original 65536! thus avoiding huge numbers. A similar strategy will be used when we work with ECs!

Groups

We saw that whenever we add two even integers, we get another one. Besides, as 0 is even and if we sum a and −a we get 0, which is the identity element for the sum. Many different objects have a similar behavior when equipped with a certain operation. For example, the multiplication of two invertible matrices results in an invertible matrix. If we consider the set of invertible matrices of N×N equipped with the multiplication, we can see that if A is in the set, A−1 is in the set; the identity matrix is in the set (and it plays the role of identity element with respect to multiplication). In other words, some sets equipped with a certain operation share some properties and we can take advantage of the knowledge of this structure. The set, together with the operation, forms a group. Formally, a group is a set G equipped with a binary operation × such that:

We can easily see that any field is, in particular, a group with respect to each one of its two operations (conditions 1, 2 and 4 for the field indicate it is also a group with respect to the sum and 1, 3 and 5 for multiplication). If the operation is commutative (that is, a×b=b×a) the group is known as an abelian (or commutative) group. For example, the invertible matrices of N×N form a group, but it is not abelian, since A×B≠B×A for some matrices A and B.

We will be interested in finite groups (those where the set contains a finite number of elements) and, in particular, cyclic groups. These are groups which can be generated by repeatedly applying the operation over an element g, the generator of the group. The n-th roots of unity in the complex numbers form an example of a cyclic group under multiplication; this is the set of solutions of xn=1, which are of the form exp(2πik/n), with k=0,1,2...,n−1. This group can be generated by taking integer powers of exp(2πi/n). The roots of unity play an important role in the calculation of the fast Fourier transform (FFT), which has many applications.

Elliptic curves in a nutshell

Elliptic curves are very useful objects because they allow us to obtain a group structure with interesting properties. Given a field F, an elliptic curve is the set of points (x,y) which satisfy the following equation:

y2+a1xy+a3y=x3+a2x2+a4x+a6

This is known as the general Weierstrass equation. In many cases, this can be written in the simpler form

y2=x3+ax+b

which is the (Weierstrass) short-form. Depending on the choice of the parameters a and b and the field, the curve can have some desired properties or not. If 4a3+27b2≠0 , the curve is non-singular.

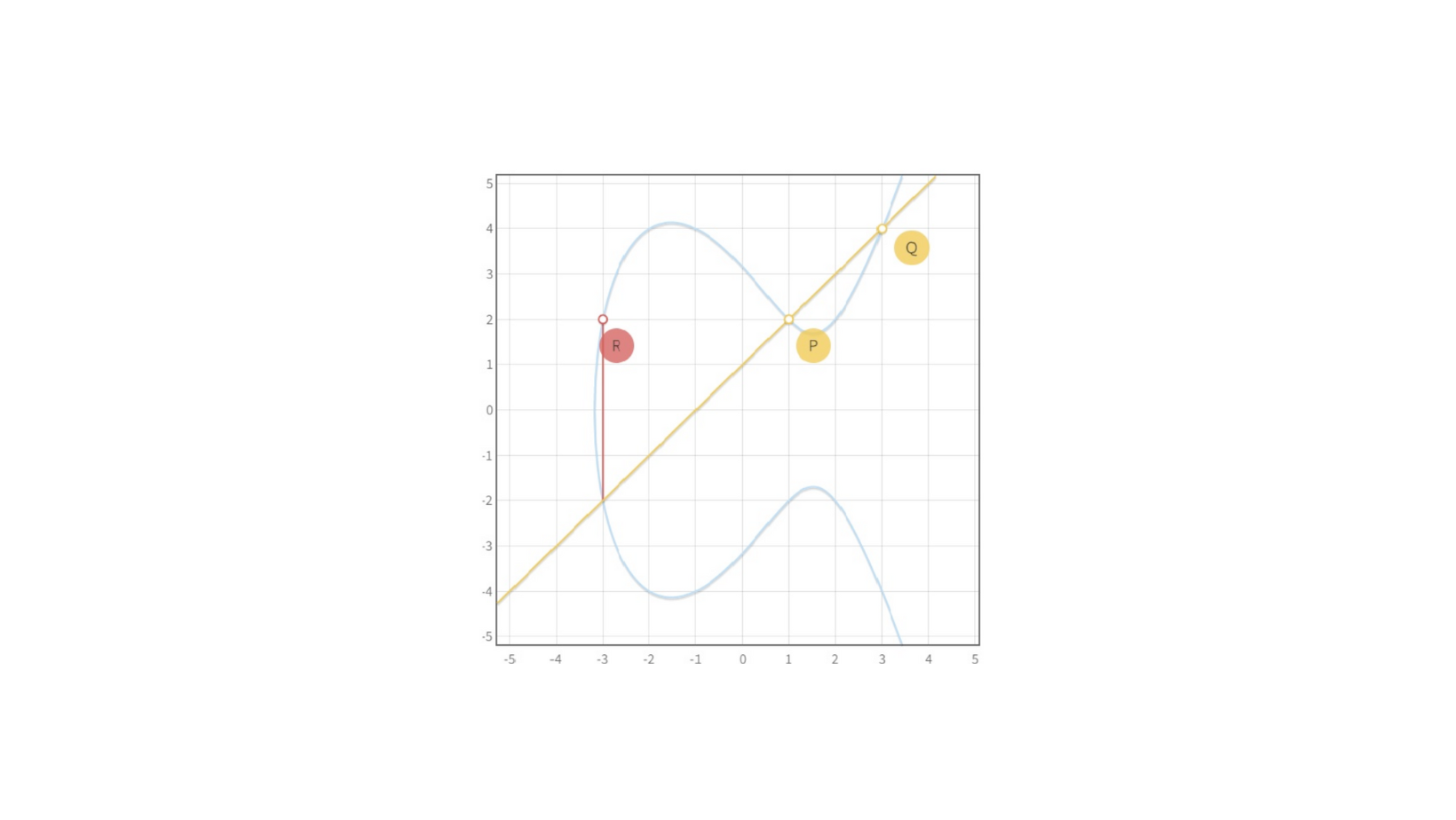

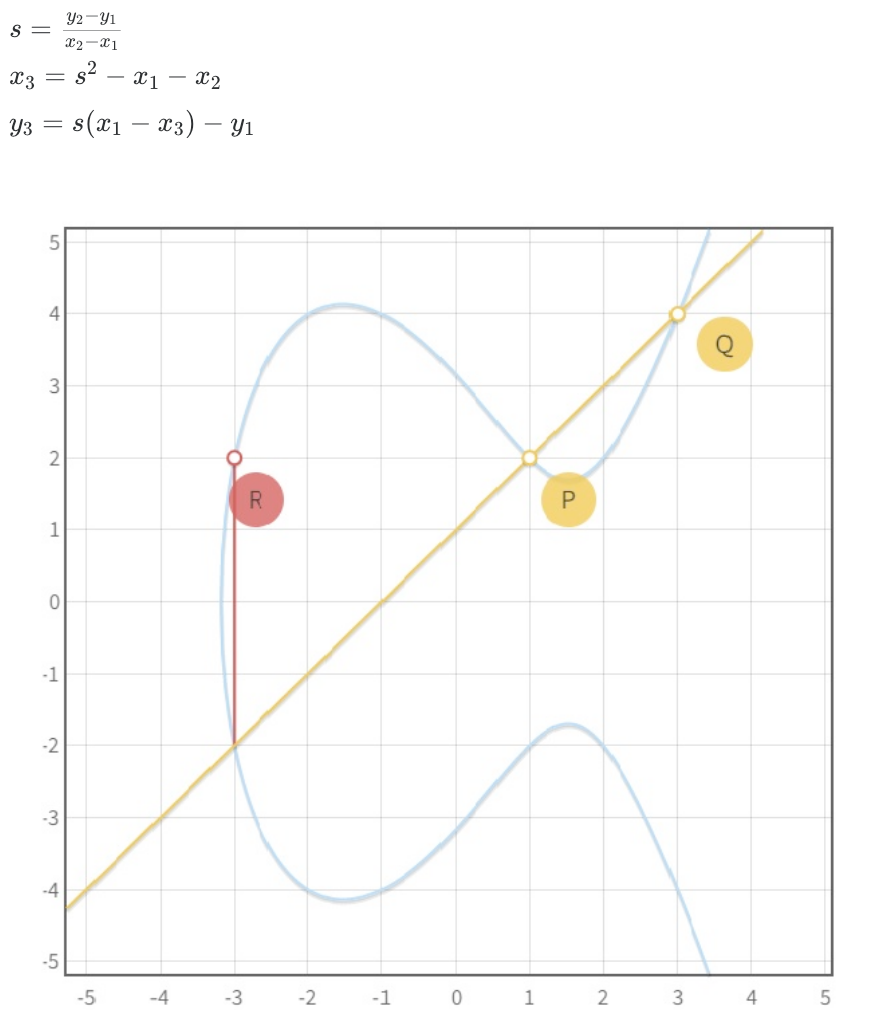

We can define an operation which allows us to sum elements belonging to the elliptic curve and obtain a group. This is done using a geometric construction, the chord-and-tangent rule. Given two points on the curve P1=(x1,y1) and P2=(x2,y2), we can draw a line connecting them. That line intersects the curve on a third point P3=(x3,y3). We set the sum of P1 and P2 as (x3,−y3), that is, point P3 flipped around the x-axis. The formulae are:

We can easily see that we have a problem if we try to sum P1=(x1,y1) and P2=(x1,−y1). We need to add an additional point to the system, which we call the point at infinity O. This inclusion is necessary to be able to define the group structure and works as the identity element for the group operation.

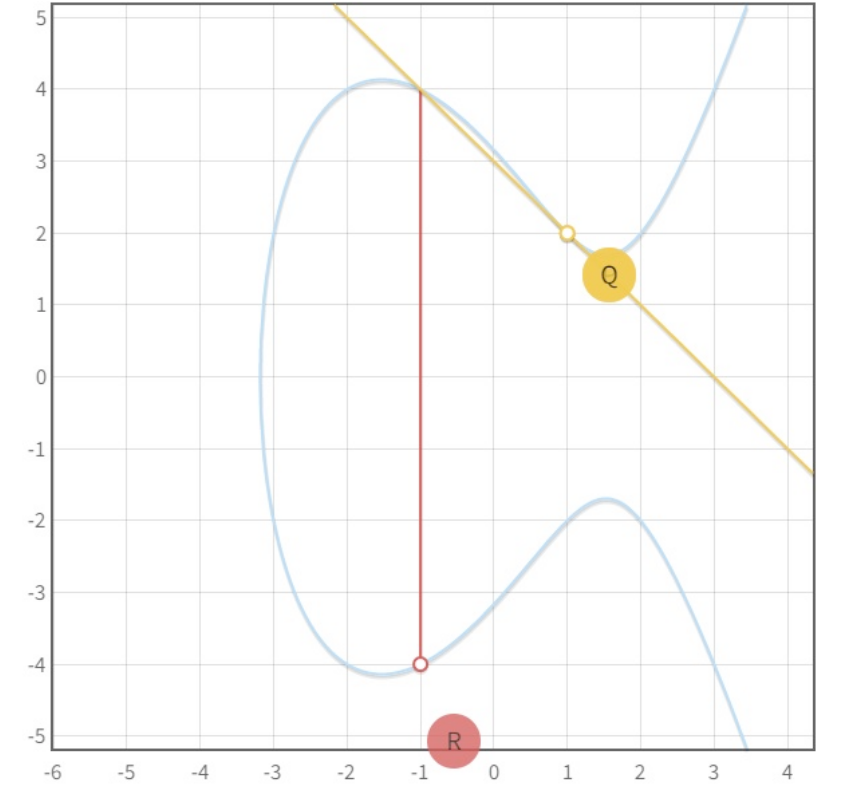

Another problem appears when we want to sum P1 and P1 to get to P3=2P1. But, if we draw the tangent line to the curve on P1, we see that it intersects the curve at another point. If we want to perform this operation, we need to find the slope of the tangent line and find the intersection:

$$s=\frac{3x21+a}{2y1}$$

$$x3=s2−2x1$$

$$y3=s(x1−x3)−y1$$

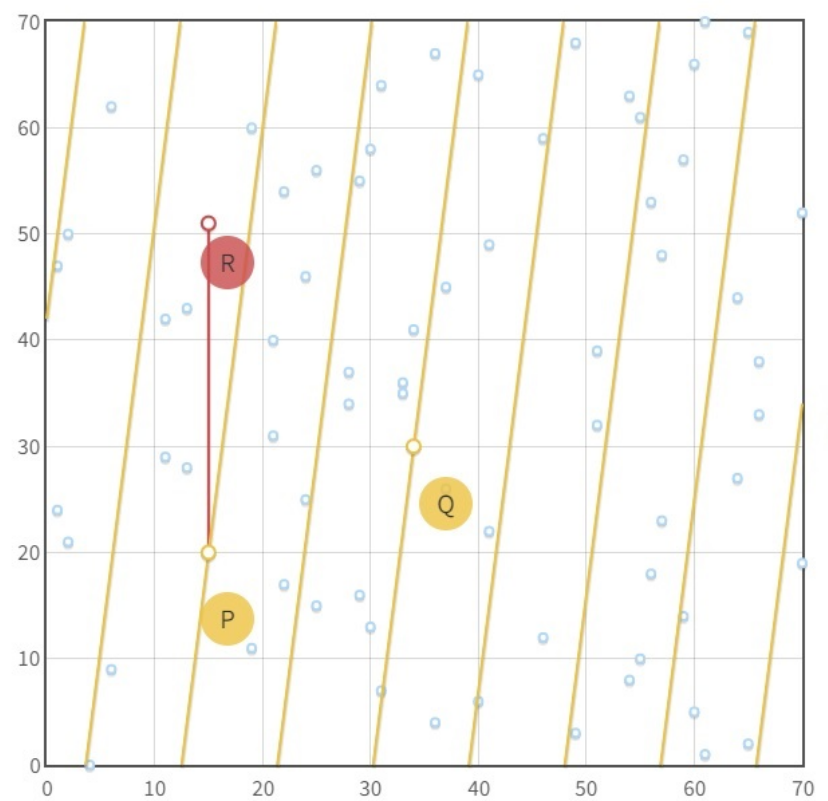

It takes a little bit of work, but we can prove that the elliptic curve with this operation has the properties of a group. We will use finite fields to work with these curves and the groups that we will obtain are finite cyclic groups, that is, groups which can be generated by repeteadly using the operation on a generator, g: g,2g,3g,4g,5g,....

If we plot the collection of points onto a graph, we see that the points are distributed in a rather "random" fashion. For example, 2g could be very far from 3g which in turn are very far from 4g. If we wanted to know how many times k we have to add the generator to arrive at a certain point P (that is solving the equation kg=P) we see that we don't have an easy strategy and we are forced to perform a brute search over all possible k. This problem is known as the (elliptic curve) discrete logarithm (log for friends) problem (other friends prefer ECDLP).

On the other hand, if we know k, we can compute in a very fast way P=kg. This offers us a way to hide (in plain sight) things inside the group. Of course, if you could break the DLP, you could get k, but it is rather infeasible. If we want to calculate 65536g, we can do it by realizing that g+g=2g, 2g+2g=4g, 4g+4g=8

Are all elliptic curves useful for crypto?

The strength of elliptic curve cryptography lies on the hardness to solve the discrete logarithm problem. This is related to the number of elements (the order of the set) making the cyclic group. If the number is a very large prime, or it contains a very large prime in its factorization (that is, the number is a multiple of a large prime), then the problem becomes infeasible. However, if the order is made up of small primes, it is possible to search over the subgroups and reconstruct the answer with help from the Chinese Remainder Theorem. This is because the difficulty depends on the size of the largest prime involved.

Some curves have desired properties and have been given names. For example, Bitcoin uses secp256k1, which has the following parameters:

a=0

b=7

p=2256−232−977

gx=0x79be667ef9dcbbac55a06295ce870b07029bfcdb2dce28d959f2815b16f81798

gy=0x483ada7726a3c4655da4fbfc0e1108a8fd17b448a68554199c47d08ffb10d4b8

r=0xfffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffebaaedce6af48a03bbfd25e8cd0364141

To get an idea on the number of elements of the group, they're about r≈1077. Even if we had 1012 supercomputers performing over 1017 search points per second for a hundred million years we wouldn't even get close to inspecting all the possibilities.

To be able to guarantee 128-bits of security, ECs need group orders near 256-bits (that is, orders with prime factors around 1077). This is because there are algorithms which can solve the problem doing operations around √r. If the largest prime is less than 94-bits long, it can be broken with help from a desktop computer. Of course, even if your group is large enough, nothing can save you from a poor implementation.

The question arises: how can we know the number of elements of our EC? Luckily, math comes once again to our aid like the Hasse bound, Schoof's algorithm and how to test whether a number is prime or not. Next time we will continue revealing the math principles behind useful tools in cryptography.